This chart shows the relative length and sequence of the various period during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

| Shunzhi 1644-61 | |

|---|---|

|

Shunzhi 1644-61

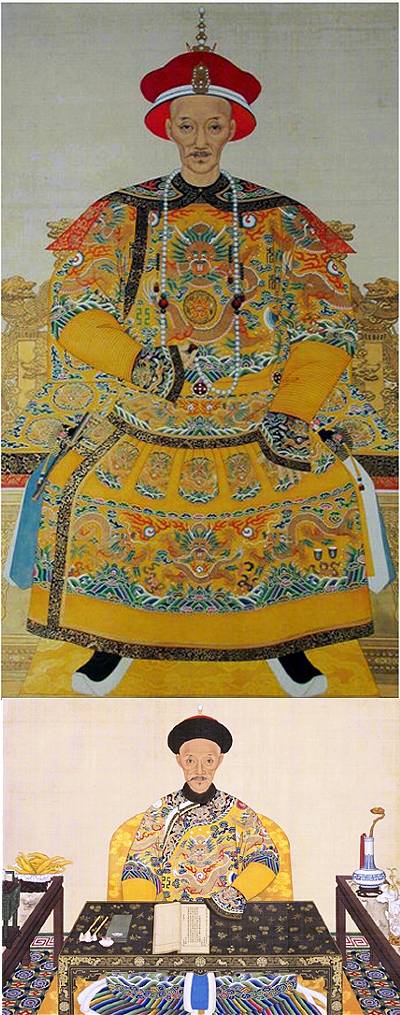

The Shunzhi Emperor's given name was Fulin. Born in March 15, 1638 he was the second emperor of the Manchu Qing dynasty and the first Qing emperor to rule over China proper. Only six when he ascended the throne the Shunzhi reign lasted from 1644 to 1661. The eighteen years of his reign brought great changes to China and its history.

Genuine Shunzhi period marks are rare if they indeed exist at all. To the left: Kaishu (normal script) style, to the right zhuanshu (archaic seal script), possibly not occuring on any porcelain before the Yongzheng period. In the first year of Shun Zhi reign (1644), a peasant army led by Li Zicheng overthrew the Ming rule in Beijing, which was in turn betrayed by traitor Wu Sangui and the Qing Army defeated Li Zicheng and occupied Beijing. Shortly, Shun Zhi came to Beijing from Shenyang and made Beijing the capital. The 5th of February in the 18th year (1661) of his reign Shun Zhi (possible) died in Yangxindian (the Hall for Cultivating Character) in the Forbidden City. In the summer of the second year of Kang Xi reign (1663), Shun Zhi's coffin was buried in Xiaoling. However, a rumor has it that he instead, heartbroken by his young wife's death, had left the forbidden city to become a Buddhist monk. Xiaoling in located at Malanyu, northwest Zunhua, Hebei Province, 125 kilometers from Beijing and is the East burial complex of the Qing dynasty. Among the tombs are the Xiaoling of Emperor Shun Zhi, Jingling of Emperor Kangxi, Yuling of Emperor Qianlong, Dingling of Emperor Xianfeng, Huiling of Emperor Tongzhi and four tombs of empresses including Empress Dowager Cian and Empress Dowager Cixi. |

| Kangxi 1662-1722 | |

|---|---|

|

Kangxi 1662-1722

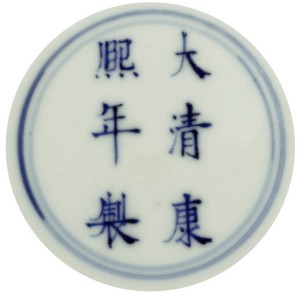

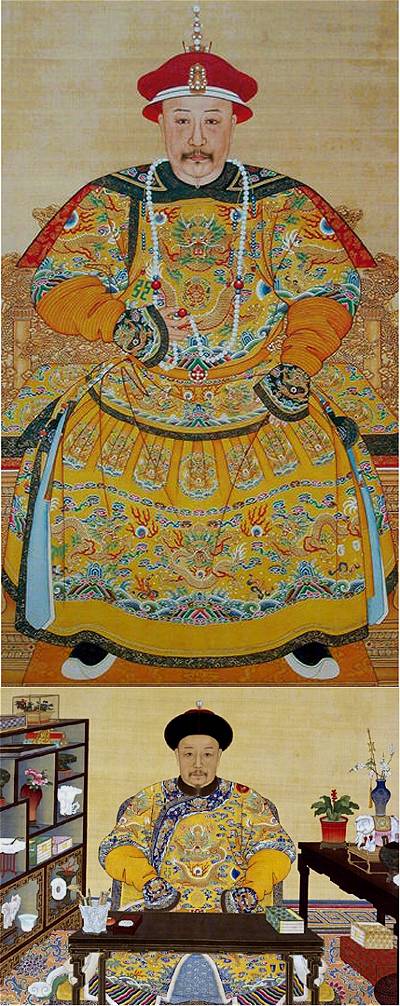

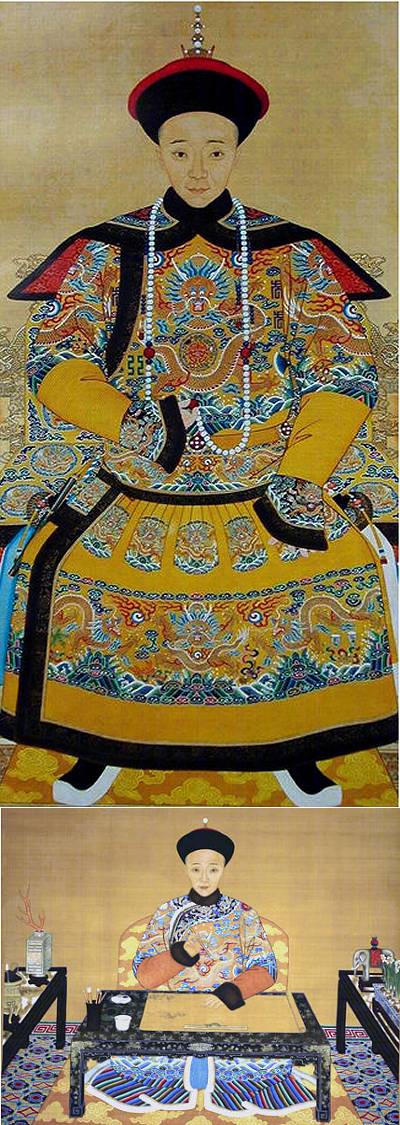

The Kangxi Emperors name was Xuanye AIXIN-JUELUO or Hiowan Yei AISIN-GIORO, in Manchu. He was born May 4, 1654 as the son of the late Emperor Shunzhi, who died in his early twenties and his mother, the 14 year old Imperial Consort Tong, a concubine from the Tongiya clan (1640 - 1663). He was the second emperor of the Qing dynasty to rule over all of China. His reign lasted 61 years, from February 7, 1661 until his death December 20, 1722, making him the longest-reigning Emperor of China in history. The Kangxi era, that is counted as full Chinese years, lasted from February 18, 1662 to February 4, 1723. The Kangxi Emperor succeeded the imperial throne at the age of seven, on February 17, 1661, twelve days after his father's death. Being too young to take power himself, the control over the empire was fulfilled by four guardians and his grandmother the Dowager Empress Xiao Zhuang, that the Shunzhi Emperor had appointed before his death to rule during Kangxi's minority. However, after a fierce power struggle one of them, Oboi, seized absolute power as a sole regent. In the spring of 1662 the Kangxi rulers ordered a massive attempt to gain control over the largely Ming loyalist southern China under the leadership of Zheng Chenggong (also known as Koxinga), something that involved moving the entire population of the coastal regions of southern China, inland. At age 15 the Kangxi emperor had Oboi arrested in 1669 and began to take control of the country himself. Of major concerns was the flood control of the Yellow River, the repairing of the Grand Canal and the Revolt of the Three Feudatories which broke out in 1673 in the south of China, and also the Chakhar Mongols rebellion in 1675. In 1673 the Kangxi government mediated a truce in the long-running war in Vietnam, which had been going on for 45 years with nothing to show for it. The Chakhar Mongols was incorporated in the 'Eight Banners' Chinese Army. In the South the incorporation of the region went so far that in 1684 the Qing Dynasty annexed Taiwan, the last outpost of Koxinga. Soon afterwards, the displaced families were encouraged to move back towards the coast. All these campaigns and many more took a great toll on the treasury. From Kangxi period's peak during the last decades of the 17th century the treasury shrunk to a tenth or less, by the end of his reign. Corrupt officials were also quite noticeable in the final years of Kangxi. The problem of dealing with this as well as the civil war in Tibet was left with some advices, to the future emperor. Eventually, through the long years of Kangxi's reign factions and rivalries had formed at the court. The Kangxi Emperor had 20 sons surviving into adulthood. Of these, his second son Yinreng was at age 2 named Crown Prince of the Great Qing Empire. After that his mother had died in childbed giving birth to him, he was brought up personally by the Kangxi Emperor to become the perfect heir to the Imperial throne. To this day, whom Kangxi actually chose as his successor is still a topic of debate amongst historians and is along with three other events, known as the Four greatest mysteries of the Qing Dynasty. In addition to his military prowess the Kangxi Emperor was famous for his scholarly abilities and his patronage of the arts. Left mark: Kaishu (normal script) style; Right zhuanshu (archaic seal script), as far as I have been able to confirm, not occurring on genuine Kangxi period pieces. Sir Harry Garner has suggested that Kangxi marks could be divided into three chronological groups on the basis of their calligraphy. Early period: bold Middle period: freely written marks, rather loose The Kangxi marks seems not to have been copied during the 18th century. One possibly explanation could be that both Yongzheng and Qianlong seems to have been busy being concerned with their own image and quite possible saw their own porcelain designs as superior to those of previous periods. In the early Kangxi period the six character Ming mark of Chenghua is seen and occasionally Jiajing, but towards the end of the reign the Kangxi six character kaishu mark is the one that is used. All genuine Kangxi period marks should be of six characters. The only genuine four character "Kangxi Nian Zhi" marks is done within a double line square border and used exclusively for palace workshop decorated wares, the highest level of Imperial porcelain. All four character Kangxi marks without borders are from and around the Guangxu (1875-1908) period when four character kaishu marks were widely used. |

Kangxi 1662-1722. Imperial Kangxi mark. Middle period: freely written marks, rather loose. |

Kangxi 1662-1722. Imperial Kangxi mark. Late period: Precise, tight, rather small and less "free" than the other two groups. |

Kangxi 1662-1722, "Da Qing Kangxi Nian Zhi" mark. During the Kangxi period, the habit of adding reign marks on porcelain not commissioned by the emperor are known to have been addressed and forbidden by public edicts. It is likely that this is an example of one of these period but not Imperial marks that these regulations was aimed at quelling. It is also worth pondering of this mark is not written by the same person as the above, but just a little bit faster. |

Kangxi 1662-1722, "Da Qing Kangxi Nian Zhi" mark. This is one of two marks from a pair of famille verte dishes, finely enameled in the center with two kingfishers flying above a flowering lotus plant. Despite the differences in calligraphy one could ponder if they are not by the same hand anyway. The decorations are identical and somewhat related to the "birthday dishes". |

Kangxi 1662-1722, Artemisia leaf mark, and of the period. During the early Qing dynasty, up until the early 1680's conditions were unsettled in China and the existence of Imperial wares as well as the use of reign marks on porcelain was restricted in various ways. During this period a number of different marks came into use, as well as two empty rings which in a way could be considered a period marking if not Imperial. |

Kangxi 1662-1722, Lingzhi fungus mark, and of the period. During the early Qing dynasty, up until the early 1680s conditions were unsettled in China and the making of Imperial wares as well as the use of reign marks on porcelain was restricted in various ways. During this period a number of other marks came into use, as well as the drawing of two empty rings on the bases which in a way could be considered a marking of the Kangxi period. Also this practice was copied during the latter part of the Qing dynasty. |

| Yongzheng 1723-1735 | |

|---|---|

|

Yongzheng 1723-1735

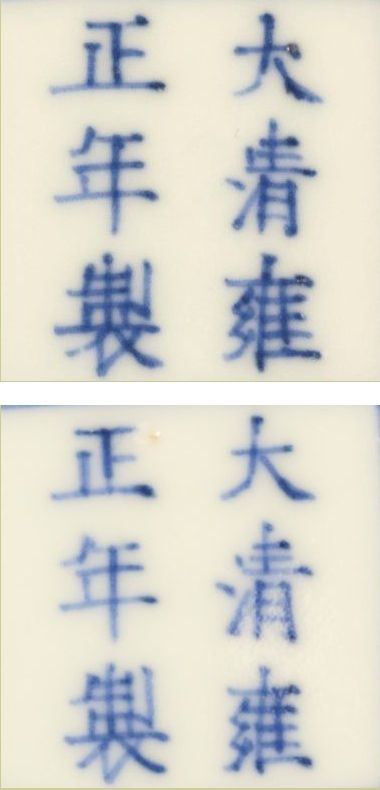

To the left: Kaishu (normal script) style mark, to the right zhuanshu (archaic seal script). |

| Qianlong 1736-95 | |

|---|---|

|

Qianlong 1736-95

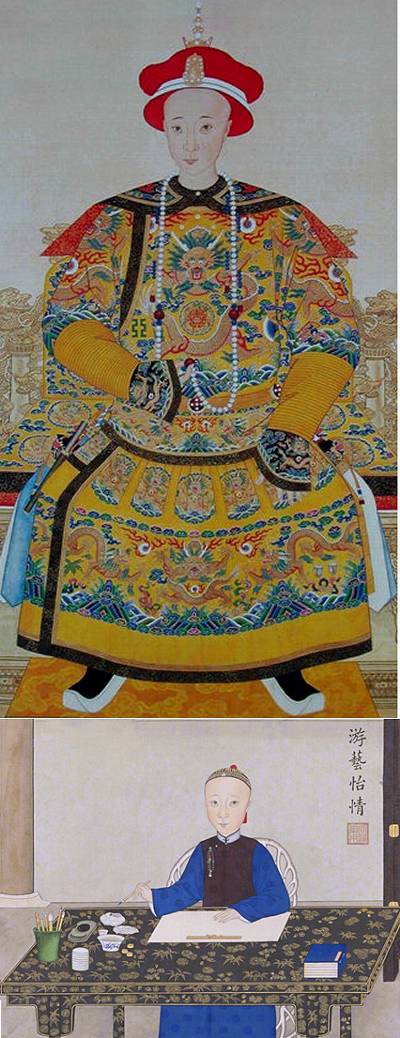

The Yongzheng emperor nominated his fourth son, Hongli, meaning "Great Successor", as his heir and he ruled from 1736 to 1796 as the Qianlong or "eminent sovereign" emperor. He had been a great favorite of his grandfather, the Kangxi emperor, with whom he would go hunting as a boy. Some say that the Kangxi emperor chose Yongzheng as his successor so that he would eventually be succeeded by his grandson, although that would seem a rather risky prospect, as the Yongzheng emperor had ten sons (though only four survived into adulthood). On a small group of porcelain genuine marks in raised blue enamel can appear. Seal marks from the period can also be written in a cartouche or with the seal broken up, and on the base of stem-cups written in a horizontal row from right to left.

|

| Jiaqing 1796-1820 | |

|---|---|

|

Jiaqing 1796-1820

During this period most imperial wares are marked with the zhuanshu "archaic seal", a continuation of its popularity from the Qianlong period.

|

| Daoguang 1821-50 | |

|---|---|

|

Daoguang 1821-50

During this period most imperial wares are marked with the zhuanshu "archaic seal", a continuation of its popularity from the Qianlong period.

|

| Xianfeng 1851-1861 | |

|---|---|

|

Xianfeng 1851-1861 The Xianfeng was proclaimed in March 1850. The first year of his reign was 1851. Died in August 1861 during the eleventh year of his reign. The Xianfeng (Universal Prosperity) Emperor, name was Yizhu AISIN GIORO. He was born in July 17, 1831 at the Imperial Summer Palace Complex, 8 kilometers northwest of the walls of Beijing as the fourth son of the Daoguang Emperor. His mother was the Imperial Concubine Quan, made Empress in 1834. Chosen as the Crown Prince in the later years of the Daoguang reign, Yizhu had reputed ability in literature and administration which surpassed most of his brothers. At age 19 he succeeded the throne, in 1850, left with a crumbling dynasty facing challenges internally and also from Europeans. In 1851 the The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Rebellion (1851-1864) began, spreading to several provinces with amazing speed. Xianfengs attempts to crush the rebellion was met with limited success. In 1855 several Muslim rebellions began in the southwest. Western forces, led by France, after inciting a few battles on the coast near Tianjin, attempted "negotiation" with the Qing Government. Under the influence of the Concubine Yi (later the Ci Xi Dowager Empress) Xianfeng believed in Chinese superiority and would not agree to any western demands. In October 18, 1860, the Imperial Summer Palaces of Qingyi Yuan and Yuanming Yuan was looted and burnt by the Western forces. Emperor Xianfeng and his Imperial entourage fled to the northern traveling palace in Jehol. While becoming more physically ill, Xianfeng's ability to govern deteriorated, while two competing ideologies in court formed two distinct factions, one under the rich Manchu Sushun, Princes Yi and Zheng; and one under the Concubine Yi, supported by Gen. Ronglu and Yehenala Bannermen. In August 22, On the 11th year of his reign (1861) at age 30 Yizhu died at the the imperial Summer Resort in Chengde, Hebei Province, (Jehol Travelling Palace), 230 km northeast of Beijing. One day before his death the Xianfeng emperor had summoned a group to his bedside, giving them an Imperial Edict to rule during his only surviving son, Prince Zaizhun minority, at that time barely 6 years old. By tradition, after the death of an Emperor, the body is to be accompanied to the Capital by the regents. Concubine Yi however traveled to Beijing ahead of time, staging a coup that would make her the acting ruler of China for the next 47 years, under the title of Empress Dowager Cixi. During Xianfeng's reign the Qing government was on the verge of collapse. In the 4th year of the Tongzhi reign (1865), Xianfeng was buried in Dingling.

|

| Tongzhi 1862-1874 | |

|---|---|

|

Tongzhi 1862-1874

The Tongzhi (To Rule Together a State of Order) Emperor, born Zaichun AISIN GIORO in April 27, 1856, became emperor at the age of five as the only surviving son of the Xianfeng Emperor and the Noble Consort Yi (Empress Dowager Cixi). He was the ninth emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and the eight Qing emperor to rule over China. During his period in practice his mother, the Empress Dowager Cixi, wielded the real power, ruling sitting behind a curtain in the audience hall. Under his reign some attempts to political reforms was made, which are know as the Tongzhi Restoration. In January 12, 1875, the Tongzhi Emperor died at age 19 of small pox without a son. It has been rumored that his cause of death was actually syphilis "due to his excessive and bizarre sexual appetite and alleged affairs with prostitutes outside of the palace". |

| Empress Dowager Cixi | |

|---|---|

|

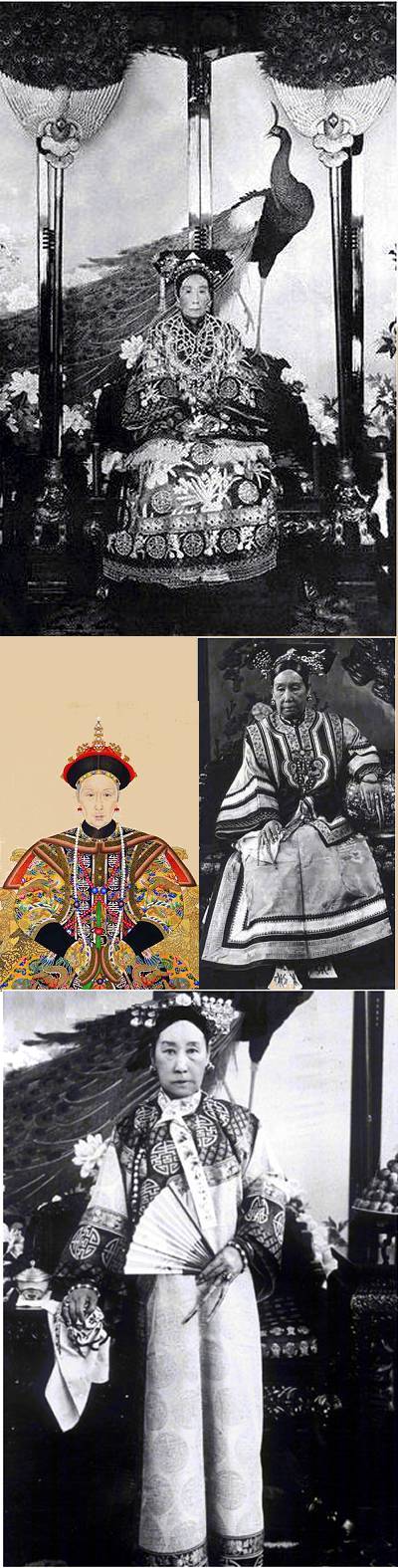

Empress Dowager Cixi

After the death of Xianfeng in 1861, Zaichun, Nalashi's six-year-old son, succeeded to the throne under the reign title of Tongzhi (1862-1874) so Nalashi was promoted to Empress Dowager with her honorary title Cixi. In the 11th year of the Xianfeng reign (1861) she worked hand in glove with her brother-in-law Yixin, launched a coup d'etat, wiped out her political enemies and commenced directing state affairs from behind a screen. Thus, she became an unofficial empress during reigns by Tongzhi and Guangxu during 48 years. Cixi died in 1908. Three years after she died, the Qing Dynasty came to its end with the Revolution of 1911. Cixi's tomb was exquisitely constructed in a unique style. It ranks as the best for building details among the tombs of the Qing Dynasty. Railings around Long'en Palace are replete with carved motifs of roaring waves, floating clouds, dragons and phoenixes symbolizing auspicious omens. The stone steps in front of the palace are carved with three dimensional phoenixes and dragons flanking the pearl. Carved on walls are intricate designs marking happiness, prosperity, and longevity. On the arch beams and ceilings are gilded golden paintings such as a golden dragon coiled around all exposed pillars. These kinds of designs are not seen in other mausoleum palaces. The tomb was plundered in 1928. The time when the Empress Dowager Cixi ruled China has among us at the Gotheborg.com site been named the Kangxi revival period since there was an obvious vogue for Kangxi style porcelain at this time. Not only blue and white pieces and enamelled porcelain in famille verte enamels were produced but also replicas in monochrome enamels such as Sang-de-Boef or Ox-blood. The good part with these early copies is that they are pretty easy to recognize since they were not really trying to produce perfect fakes, but appears to have more wanted to continue to make pieces in the Kangxi period style and tradition. Now that turned out quite difficult. Many processes and traditions were never written down and had been lost and forgotten. Sources for paste and glaze had changed. While the blue and white porcelains turned out pretty good, the red ox-blood monochromes got a too thick glaze that ran and often needed to be ground off of the foot rim. For other style replicas there were other problems making them distinguishable. Another aspect is, that there was indeed a great interest in the West, in particular among American collectors, for antique Chinese porcelain at this time. Prices at auctions were soaring. So, there was a ready market for antiques, even newly made ones. I don't think this was among the main reasons why the Kangxi period was revived as a whole, but it was a part of the picture why so many grand pieces was made. |

| Xuantong 1909-1912 | |

|---|---|

|

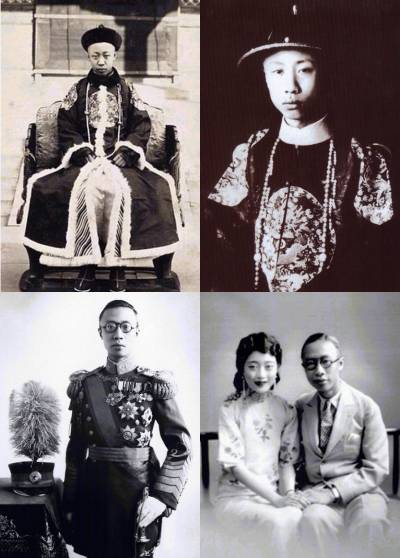

Xuantong 1909-1912 Puyi (Wade-Giles P'u-I), also called Henry Puyi, reign name Xuantong, was the last emperor (1908-1911/12) of the Qing (Manchu) dynasty (1644-1911/12) in China and pro forma emperor of the Japanese-controlled state of Manchukuo (Chinese: Manzhouguo) from 1934 to 1945. He was born Feb. 7, 1906, Beijing, China. His father was the second Prince Chun, brother of the Emperor Guangxu and nephew of the Empress Dowager Cixi, who had been the de facto governor of China for many years; her son Guangxu being mostly isolated from all governmental and family affairs. Puyi died October 17, 1967, Beijing. In 1909 Puyi succeeded to the Manchu throne at the age of three, when his uncle, the Guangxu emperor, died on Nov. 14, 1908 and reigned under a regency for three years. In 1911 the Qing dynasty was overthrown and China declared to be a republic. When the republicans occupied Peking they required the abdication of Puyi but guaranteed his title, safety, income, etc., in the Articles of Favorable Treatment which was accomplished on February 12, 1912. Thus the Republic of China despite many competing warlord armies came into being, with the recent Imperial general Yuan Shikai, becoming President. Thus, Puyi was ruling emperor until February 12, 1912 (and also briefly between July 1 and July 12, 1917), and non-ruling emperor between February 12, 1912 and November 5, 1924. In 1924 he left Beijing to reside in the Japanese concession at Tianjin. In March 9, 1932-1934 Puyi was put in place as the leader of the Japanese-controlled Manchukuo in Manchuria (China's Northeast) under the reign name Datong and in 1934 to 1945 made 'emperor' of the same region under the reign title of Kangde. |

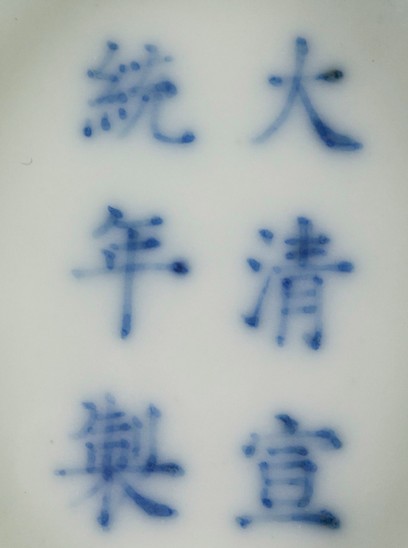

| Xuantong 1909-1912, kaishu mark in regular script. Accepted by Sotheby's as genuine in 2013. Demonstrates clearly a feature that is often called hollow or fractured, line. The decoration of the piece, iron red bats among clouds is in a distinctly different style as compared to similarly decorated pieces of the previous reign. |

| Hongxian (Yuan Shikai) 1915-16 | |

|---|---|

|

Hongxian (Yuan Shikai) 1915-16

|

The marks section of Gotheborg.com was initially established in May 2000 thanks to a generous donation of approximately one hundred images of Japanese porcelain marks, by Karl-Hans Schneider from Euskirchen, Germany. This contribution provided a modest yet substantial beginning of the Marks Section. It was a kind gesture that I really appreciated.

Of the many later contributors, I would especially want to mention Albert Becker, Somerset, UK, who was the first to help with some translations and comments on the Japanese marks. His work was then greatly extended by Ms. Gloria S. Garaventa, after which Mr. John Avery looked into and corrected some of the dates. Most of the Satsuma marks were originally submitted by Ms. Michaela Russell, Brisbane, Australia. A section which was then greatly extended by Ian & Mary Heriot, a large amount of information from which still awaits publication.

A warm thank you also goes to John R. Skeens, Florida, U.S.A., and Toru Yoshikawa for the Kitagawa Togei section, and to Susan Eades for her help and encouragement towards the creation of the Moriyama section. For the last full overhaul of the Satsuma and Kutani sections, thank you to Howard Reed, Australia. The most recent larger contribution was made by Lisa M. Surowiec, New Jersey, USA.

In 2004 and from then on, my warm thank you goes to John Wocher and Howard Reed, whose knowledge and interest have sparked new life into this section and given reason for a new overhaul. Thank you again and thank you to all I have not mentioned here, for all help and interest in and contributions to our knowledge of 20th-century Japanese porcelain.

The Chinese marks section would not have been possible without the dedicated help of Mr. Simon Ng, City University of Hong Kong, whose translations and personal efforts in researching the origin and dates of the different marks have been an invaluable resource. It has since been greatly extended by several contributors such as Cordelia Bay, USA, Walt Brygier, USA, Bonnie Hoffmann, Harmen Lensink, 'Tony' Yalin Zhang, Beijing, 'ScottLoar', Shanghai, Mike Harty, and many more expert members of the Gotheborg Discussion Board.

A number of reference pieces have also been donated by Simon Ng, N K Koh, Singapore, Hans Mueller, USA, Hans Slager, Belgium, William Turnbull, Canada, and Tony Jalin Zhang, Beijing.

All images and text submitted by visitors and published anywhere on this site are and remain the copyrighted property of the submitter and appears here by permission of the owners which can be revoked at any time. All information on this site, that are not specifically referenced to peer reviewed sources, are the personal opinions given in good faith by me, my friends and fellow experts, based on photos and the owners' submitted descriptions. They are not to be used for any financial or commercial decisions, but for educational and personal interest only, and can and will be changed as further information merits.

For further studies, Encyclopedia Britannica is to be recommended in preference to Wikipedia, which, not being peer-reviewed, might contain misleading information.

Web design and content as it appears here © Jan-Erik Nilsson 1996-.